About Macular Degeneration

Macular degeneration, also known as age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a common condition in older adults and the leading cause of vision loss in people over the age of 65. Macular degeneration affects the macula, the part of the retina responsible for sharp, detailed vision needed for reading or driving. As one ages, the retinal tissue responsible for central vision slowly begins to deteriorate, and this change can significantly affect a patient’s quality of life.

Types

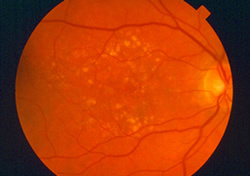

Macular degeneration can be classified as either wet (neovascular) or dry (non-neovascular). Dry macular degeneration is the more common diagnosis, and is considered to be an early stage of the disease characterized by the development of aging deposits called macular drusen and the deposition of pigment under the retina. If the disease progresses, the retinal vision cells and their underlying supportive pigmented layer will degenerate, producing geographic atrophy, the disappearance of the retinal tissue.

Only about 10% of patients see their condition progress to the more advanced and damaging wet macular degeneration. In wet macular degeneration, new blood vessels develop beneath the retina and cause leakage of blood and fluid under the retina. This leakage can lead to permanent damage of central vision and the creation of blind spots. Although it’s the less common form, wet macular degeneration, until recently, has been responsible for nearly 90% of the cases of severe vision loss caused by AMD.

Symptoms

Patients with dry macular degeneration may notice gradual changes in their vision, including shadowy areas in the central vision, or fuzzy and distorted vision. These areas grow larger as the disease progresses, and can eventually turn into blind spots if geographic atrophy develops. Patients may also have difficulty seeing color and fine details.

If the disease advances to the wet form, patients more commonly may also see straight lines as wavy or new blurry spots. With wet macular degeneration, the central vision loss can occur rapidly, sometimes within a few days or weeks.

Patients with a family history or diagnosis of AMD can monitor their vision at home using an Amsler grid test. Other home-based electronic systems, now commercially available, may be useful in patients with signs of disease which place patients at higher risk for vision loss.

Diagnosis

Your ophthalmologist can detect early signs of AMD, before the onset of symptoms, through a dilated retinal examination using special magnifying lenses, which provide a three-dimensional, stereoscopic view of the macula. Additional testing may involve high-resolution digital photography, a special type of retinal scan called Ocular Coherence Tomography (OCT), or Intravenous Fluorescein Angiography (IVFA) – a study which uses a contrast dye, injected into an arm vein, to outline the retinal blood supply for special photographs.

Causes and Risk Factors

Many factors have been recognized to increase one’s risk for AMD. These include age (typically over 50 years), smoking, high blood pressure, prolonged sun exposure, high-fat diet, and genetic factors. Variants of the gene which codes for complement factor H recently have been implicated in nearly half of the sight-damaging complications of AMD. Active research continues to reveal other genetic factors.

Another chemical, Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor or VEGF, is a major cause of abnormal blood vessel growth typical of the wet form of AMD. It now represents a major target for treatment.

Treatment

While there is no cure for AMD, there are several treatment options available to help manage patients with this condition and preserve vision. The options for treatment depend on the type of AMD, its severity, and the patient’s vision potential.

Anti-oxidant multivitamin therapy, as established by the Age Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS I) has been shown to slow progression of AMD by limiting the oxidative damage under the retina and, at this time, represents the only treatment for dry AMD. Additional information regarding adjustment in the dosing and types of multivitamins will be reported from the ongoing AREDS II trial in the near future.

Intraocular injections of bevacizumab (Avastin), ranibizumab (Lucentis), and aflibercept (Eylea) are most commonly used to treat the wet form of AMD. These drugs target VEGF in varying degrees and allow control of abnormal blood vessel growth beneath the macula. Studies have shown that these medicines should be continually injected to achieve and maintain the best visual results since at this time there is no cure for the disease. It should be noted that the frequency and duration of injection treatments is highly variable. The treatment approach adopted must be customized to the each patient’s activity and severity of macular disease. In selected cases, observation may be the most appropriate management based on the judgement of your doctor.

Photodynamic Therapy (PDT) involves the intravenous (IV) delivery or infusion of a special infrared light-sensitive dye, which selectively collects in the abnormal blood vessel tissue under the macula. Shortly after the infusion, a non-thermal infrared laser is targeted into the eye through a special magnifying contact lens. The laser activates the medicine resulting in closure of the treated blood vessels under the macula. While more commonly used some years ago, recent studies have shown that, in selected cases, PDT still can be a useful strategy when combined with injection treatments in the eye.

It is essential for patients with AMD to be monitored and managed as indicated for their condition since timely intervention can stabilize vision and reduce the risk for severe vision loss.

Please call our office at 301.571.2000 to learn more about macular degeneration or click here to schedule an appointment.